Reflections: Eyes That Kiss In The Corners

It’s about what we can do.

I am acutely aware that this is being written and will be published within a political climate currently taut with suffering and pain from the increase of racially-motivated attacks on ESEA people, particularly the Atlanta Spa shootings that occurred on the 16 March 2021. Though this piece initially began as a review of Eyes That Kiss In The Corners, it evolved into the self-exploration, I suppose, of why we must continue to have this conversation about what literature - even children’s literature - means for opacity. In the first half, I briefly look at how I interpret an aspect of Joanna Ho’s book that pioneers our opacity in nuanced representation. The second is more of a digression than anything else: a look into what it means to me to have books like Eyes That Kiss.

“… as she earnestly looks out to her readers”

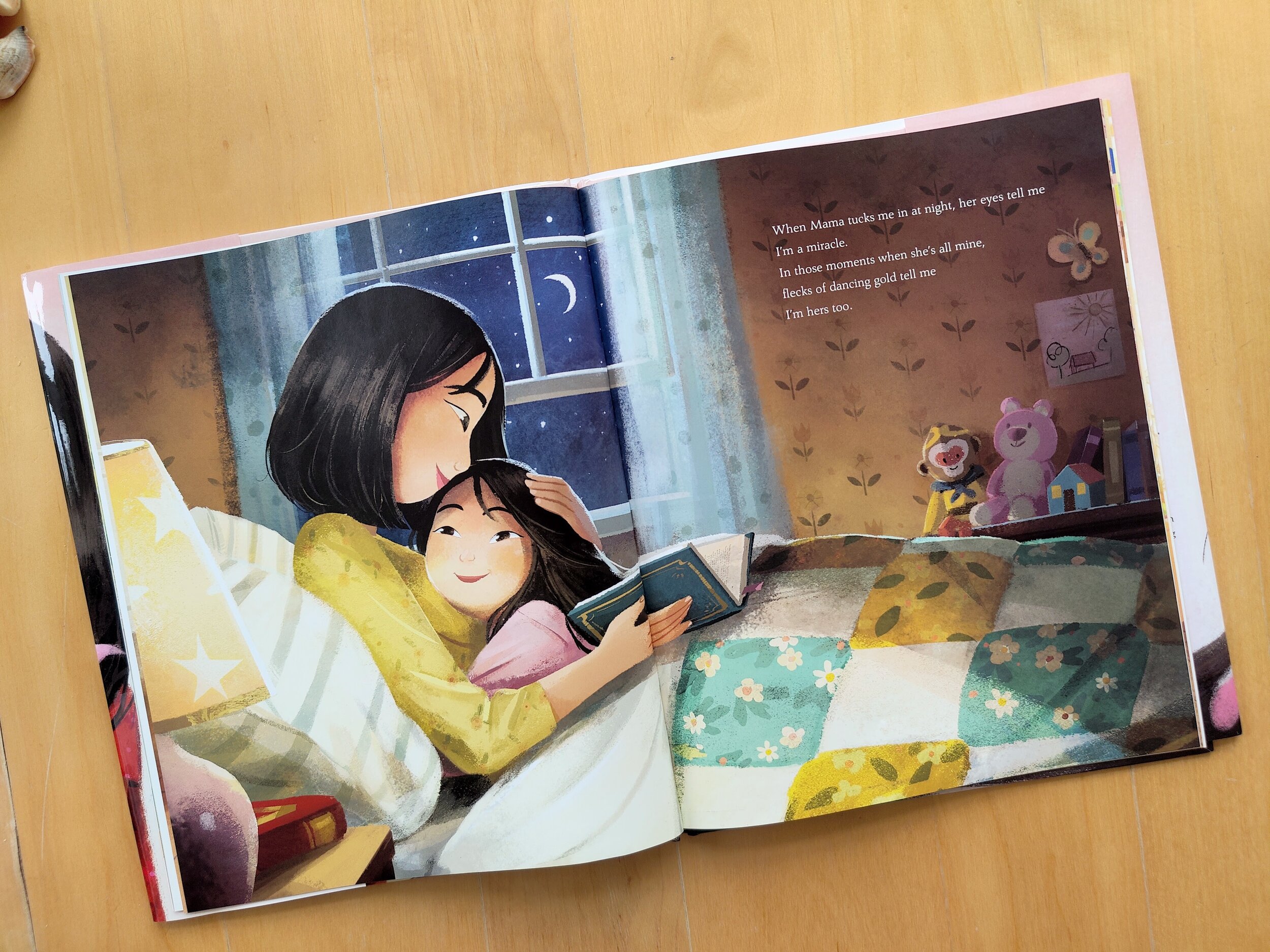

In a book about celebrating self-respect and individual beauty, eyes are not the focus, despite the title. While eyes form the basis of the book, they give us the platform to explore the actions and the significance of the characters they introduce. The eyes that ‘kiss’ and ‘glow’ are a synecdoche of the girl’s sense of self and animates her as she earnestly looks out to her readers in the third page. In a literary culture that has rendered this girl static, this single refrain returns each time to add another layer to the girl’s sense of individuality. Every layer builds upon the history, culture and familial devotion that forms a significant part of her self-image. So, it is interesting that these eyes are able to ‘kiss’, forming a junction where past and present are in a sweet dialectic - creating a site of reckoning and reconciliation that emerges as forward progress.

“Every layer builds upon the history, culture and familial devotion that forms a significant part of her self-image.”

At the girl’s first appearance, her eyes are therefore not only beautiful and striking, they invite the reader to consider the people behind each pair of ‘eyes that kiss in the corners and glow like warm tea’. The static, silent eye is animated with the verbs of communication, welcoming the reader with tenderness and warmth and leading them into a world where they may, too, have a voice to share. These eyes take unto themselves the actions and the words of the voice behind the book and add another dimension to our representation. This book ‘clamo[u]r[s] for the right to opacity’ by not simply requesting a voice and your ear, but asking that you look - to see her clearly against the background.

And to reiterate, it does precisely this. Its message is twofold: the author asks that you listen to the voices behind the community she represents; the girl asks that you acknowledge her individuality and distinction.

“The lyrical words and beautiful images use the eyes to reveal the background behind each character and, through their signification, make each character opaque - visible - undeniable.”

The final illustrations build this opacity of the individual with a story of progression and forward movement. The book develops its flora with every character it introduces, beginning with the simple blossoms on Mama’s sleeping clothes, the peonies that accompany Amah, the plum blossoms that frame Mei-Mei’s window and finally the phoenix’s tailfeathers bursting from the girl’s imagination. In the penultimate illustration, the plain white background upon which she was first introduced is brought to life by the overflowing flower arrangement. Each layer of this arrangement represents a part of her identity which she described through her relation with her family. Her background is, literally, neither white nor negligible. In fact, it reaches out into the foreground, fringing her hair and shoulders, in a bouquet that uniquely defines her own image as an amalgamation of the actions that vivify her heritage, her culture, and her relation with her world. These flowers are no longer rendered transparent by the end of the book. The lyrical words and beautiful images use the eyes to reveal the background behind each character and, through their signification, make each character opaque - visible - undeniable.

What it means to be opaque.

I brought up a quote from Édouard Glissant’s ‘For Opacity’ and I wish to use this framework to draw some lines of thought to my personal reflections about ESEA representation in the media and in literature.

In a very rushed summary of the essay, we could argue that Glissant’s idea of opacity is the right to be recognised and to be rendered visible in more nuanced representations. To describe this, he very aptly presents society through the metaphor of a woven fabric where ‘one must focus on the texture of the weave and not on the nature of its components’ in order to understand the complexity and beauty of it.

In essence, rather than extending representation as a form of violence that reduces the individual to a transparent state within which we are appeased and silenced, society should use representation to give voice to and embrace difference. Again: rather than being afraid of our differences and seeking to eliminate them so that they are rendered transparent on this background, we must learn that our ideas of difference are things that make our society stronger. So, when reading inclusive children’s literature, the act of reading is not enough, just as the eyes are only an signifier for the larger whole - the girl’s undeniable identity. The representation we strive for cannot only be a representation that seeks to measure individuals up against a standard, that seeks to ‘grasp’ our being and make it transparent. So, it is important that our act of reading continues to strive for the opacity of the individual - for the right to be understood opaquely.

So, that is why having books like Eyes That Kiss, championing these differences and representing them in our children’s literature to foreground these discussions, is pure joy. And it’s also why being able to sell books that support households embracing bi- or multilingualism is our honour. The next generation shouldn’t grow up believing that their language or culture makes them Other, or the value of their existence should be compared against a standard. We shouldn’t be afraid of our differences and recent events only prove that there are still things we can do.

You may see this as a plea, and I suppose it is. A plea to my readers that we may all take the steps to collaborate on a future where difference is beauty: cherished and unafraid. I know sometimes some feel completely helpless and emotionally drained, but we can channel our energy to ensure that our representation is not reactionary. The representation we seek is actively, joyfully and painfully formed and we must include the wider community in it in order to achieve this future free of fear. So, in all that we do, may we strive to do them out of a love and respect for each other’s opacity.

A note about this review… Please take a little time to read this disclaimer.

I will point out that, Glissant is a Martinican writer whose commentaries on the racial and cultural dynamics in the francophone world are from the perspective of one affected by the African diaspora. Though I can’t even imagine some of the battles faced by those in the African diaspora, I am in constant admiration of the social and cultural critique that postcolonial theories enable. I recognise that our experiences of the postcolonial world are different, but we are united by a single belief. Our differences shouldn’t make us feel ashamed of who we are - regardless of what is portrayed in the media or by our peers. We should strive to create representations of ourselves that deliver nuance and individuality and reckoning, like ‘eyes that kiss’.

EDIT (23/03/2021): After watching and listening to Joanna Ho’s thoughts on the use of inclusive children’s literature (see here), I’ve since reread this article and decided to add some elaborations to ‘What it means to be opaque.’. I want to clarify that representation should be nuanced. It should result in amplification, not reduction, and the way we can do this is by using literature to foreground these issues and discuss them in the open. Differences should be the norm rather than perpetually remaining as ‘Other’. Otherwise, we need to revise the standards against which individuals are measured.

References

Édouard Glissant, ‘For Opacity’, in Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (1990; Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997).

If you’ve managed to make it this far into this post, then I’d like to extend my heartfelt gratitude for reading all the way through. The changes I had to make to this initial review were made in the matter of a couple nights, and is far from a comprehensive view on representation of the ESEA community. So, if you spot any mistakes, even if it’s something like a typo, please let me know!

For those looking for resources and ways to support, I’m including some links below:

Amazing resources: @besea.n, @britishvietproject, @asiankidlit, @beingbrasian, @dearasianyouthlondon

Literature and arts: @rumah.khai, @beseapoets

Business catalogues: @britishchinesebiz

Buy Eyes That Kiss In The Corners: from De Ziremi, from Bookshop

I’d also really encourage you to read Glissant’s ‘For Opacity’ if you manage to have access to it. It’s a short essay and a compelling read.

Once again, thank you ever so much for reading this. I pray we can use our collaboration and love to build a brighter future for our children.